In the fall of 2009, while sorting through a tank of young Ocellaris clownfish (Amphiprion ocellaris), several unusual fish were discovered by one of our hatchery technicians.

These fish were larger than their Ocellaris tankmates and exhibited unique coloration and shape. Their overall appearance was Ocellaris-like however they seemed to exhibit traits from both Ocellaris and Maroon (Premnas biaculeatus) clownfish. It appeared that these fish were hybrids and because they were mixed in a tank full of Ocellaris it was presumed that they originated from a male Gold Stripe Maroon Clownfish and a female Ocellaris Clownfish. Interestingly, we did not have these two species paired up with one another in our facility. Although this wasn’t the first time we had found truly unusual clownfish in our growout systems it was, and still is, an extremely uncommon occurrence.

There are several possible explanations for these unusual fish. The first and least likely scenario is that these fish are some sort of chimera that is randomly produced and is a fast-track to a new species. Another scenario is that these fish are a throwback that has been maintained in our clownfish gene pool and happened to pop up when gametes, from two individuals possessing these genes, produced a viable organism of an ancestral type. Examples of this include humans born with a vestigial tail or dogs born with extra dewclaws.

While we wouldn’t dismiss these two possibilities entirely, it seems much more likely that these hybrids are the result of cross fertilization. What makes this a more likely scenario is the fact that Clownfish are demersal spawners who fertilize their eggs externally. Our broodstock systems house multiple pairs of fish spanning several different genera. In the case of the Ocellaris and Gold Stripe Maroon hybrid, we suspect that the sperm of a male Gold Stripe Maroon, who was spawning with his mate, fertilized the eggs of a female Ocellaris that was spawning at approximately the same time but in a different tank within the same system.

That possibility would seem far fetched even if the fish were in the same tank, but in order for the cross fertilization to occur, the sperm of the Gold Stripe Maroon had to travel through the plumbing and filtration system and then be pumped into the tank containing the spawning Ocellaris pair. Once the Gold Stripe’s sperm made it into the Ocellaris tank it had to beat the male Ocellaris’ sperm to the egg! Incredible!

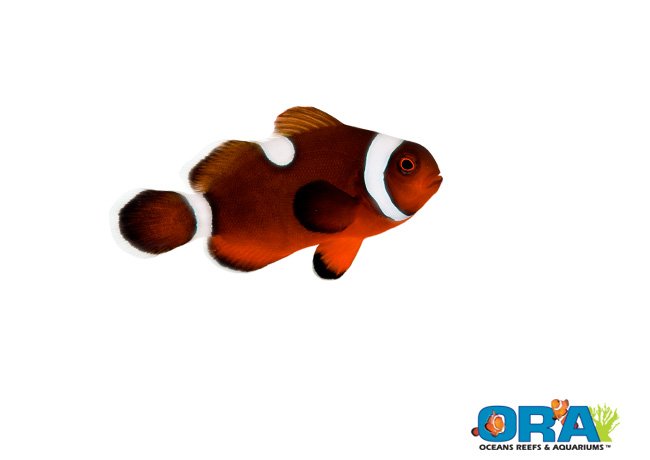

Not long after the “Gold Stripe Ocellaris” was discovered, similar individuals were discovered in a Gold Stripe Maroon growout tank. In this case it appeared that the parentage was reversed, with the female being the Gold Stripe Maroon and the male an Ocellaris. These fish inherited more of a Gold Stripe Maroon appearance.

Other unintended hybrid clownfish we’ve found include what appears to be a Gold Stripe Maroon and Tomato (Amphiprion frenatus) hybrid, an Ocellaris and Clarkii (Amphiprion clarkii) hybrid, and an Ocellaris and Tomato hybrid. Recently another apparent hybrid was found in an Ocellaris growout tank, it’s parentage has us stumped. Each of these hybrids are unique in appearance and tend to inherit more of their mother’s general appearance, but they all seem to grow faster than their purebred siblings, possibly as a result of hybrid vigor.

It may seem nearly impossible for hybrids to occur like they have in our systems. However, when you consider the concentration of sperm, following a spawning event, in the water flowing through our systems compared to the concentration that would be found in the ocean, combined with the swimming nature of sperm in a fluid environment, it may not be as unlikely as one might expect. Hybrid pairs of Clownfish have been photographed in the wild but the notion that sperm remains viable after so much trauma and distance means that hybrids could be produced just by being in the same proximity. This should add fuel to the fire over the two questionable clownfish species, A. thiellei and A. leucokranos.

We have encountered some difficulty incorporating these hybrid fishes into our breeding program. Fishes from the same hybrid cross pair up fairly easy and they seem to recognize each other as the same type of animal. However, when we attempt to pair a hybrid individual with an individual from either of the hybrid’s parent species the two fishes rarely get along well enough to form a pair bond. The hybrid fishes seem a little too pushy for the other fish we attempt to pair them with. To date, the only fish we’ve witnessed laying eggs is a female that appears to be a hybrid between a Clarkii and an Ocellaris that was paired with a similar looking male. The eggs did not last more than a day so we’re unsure if they were viable or if the male had even fertilized them.

It is not yet known if our other unintended hybrid individuals are capable of producing viable gametes or offspring; only time will tell. While the Maroon and Ocellaris clownfish have been crossed before, creating hybrid pairs of clownfish is a challenging process especially in the confines of a broodstock aquarium. Many times, different species of clownfish seem to speak a different language with their bodies and mouth parts and will not live as a harmonious pair, let alone spawn with one another. Hybridizing clownfish has not been a goal of ours, to date the only luck we’ve had producing hybrid clownfish intentionally was from pairing a male Tricinctus (Amphiprion tricinctus) with a ready-to-spawn female Clarkii.

Not only are these hybrid fishes extremely unique and in many cases beautiful, their existence helps to stimulate thought about the evolution of clownfish and the role their reproductive biology plays on their evolution. For example, since it seems the hybrid fishes will not pair up easily with individuals from either of their parent species, could this be the result of mechanisms that typically prevent hybrid pairs from forming, such as chemical cues, behavior biology or body color and pattern preference? And if, in the wild, two hybrid fishes produce viable offspring that are capable of reproduction, could this produce an isolated breeding population of hybrid fishes that are unwilling to pair up with fish of different phenotype and be a fast track to the formation of new species?

Designer clownfish are here to stay and once hybrids enter the scene, it will become the responsibility of those breeding these fishes to maintain detailed genetic histories. There is potential in utilizing artificial means of fish propagation to create hybrids, through the use of hormones or strip spawning, but we have yet to take such drastic measures. Until we are able to find a way to produce hybrids regularly, we’ll just have to enjoy the occasional but miraculous few that pop up every now and then in our growout systems.

UPDATE 4/17/2013 – We added a picture of a new hybrid clownfish that popped up. This fish was found mixed in with Black Ocellaris and because of its similarity to the Clarkii x Ocellaris hybrid pictured above we think it was produced by a female Black Ocellaris and an male Clarkii.

Check out the gallery below, for some additional images of these fishes: